Summary: Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and the other small wars we have and are fought. All fruitless in terms of our nation’s needs. All fought at great personal cost by our troops, up to and including the ultimate payment. But no nation can continue to waste the valor of its troops in such a manner without eventually having a reckoning. These are men and women, among America’s best. Eventually they will ask questions. Perhaps they’ll demand a change in the national equation. Today we look at one moment from history described by historian Beth Crumley, a note about wasted valor.

.

“Fire Support Bases Neville and Russell, 25 February 1969“, Beth Crumley

Originally posted at the Marine Corps Association website on 15 February 2012. Reprinted here with their generous permission.

.

Over the years I have often talked about Vietnam. How it’s looked at differently than the wars that preceded it. When I addressed the 1st Battalion, 4th Marines in October, I began by asking a simple question: “I am sure that most of you here today were at least aware of some of the history of this battalion before today. The history of this battalion is the stuff of legends…but how many of you sitting here today know anything about the history of this unit in Vietnam?” The only person to raise his hand was an older gentleman, a guest who had obviously served in Vietnam himself.

I was not surprised. As I said to the assembled Marines, we tend to embrace the history of World War II, and to a lesser extent Korea — but not so much Vietnam. Why is that? Probably because it isn’t easy. The war in Vietnam was not marked by set-point battles, or large-scale amphibious assaults against enemy held beaches. Instead it was one named operation after another, endless patrols, and search and destroy missions that blended together into “the War.”

So what was the situation faced by the Marine Corps in January 1969?

.

Enemy activity in Northern I Corps was described as “light” and “sporadic.” Along the DMZ, units of the 3d Marine Division faced elements of six North Vietnamese regiments. Enemy activity was generally limited to occasional rocket and mortar attacks on allied positions, ground probes by squad and platoon sized units, and attempts to mine the Cua Viet River. In the central portion of Quang Tri Province, units of the NVA’s 7th Front and the 812th Regiment had largely pulled back into jungle sanctuaries for resupply and replacements. Further south in I Corps, the situation was similar. NVA units had withdrawn into the A Shau Valley and Laos.

While the enemy generally avoided contact, American and South Vietnamese forces operating in northern I Corps continued their efforts to keep the enemy off balance. They struck at traditional base areas and infiltration routes, and increased security within populated areas.

Leading the American effort in Quang Tri Province was the 3d Marine Division under the command of Major General Ray Davis. Davis has been described as a “Marine’s Marine.” He was a veteran of Guadalcanal, Cape Gloucester, and Peleliu. He was awarded a Medal of Honor for leading a contingent of Marines through bitterly cold temperatures, snow, and wind to relieve the beleaguered men of Fox Company at Toktong Pass during the breakout from Chosin during the Korean War. Now, under Davis’ leadership, tactical disposition of the 3d Marine Division was turned upside down.

When he took command in May 1968, much of the 3d Marine Division was tied down to combat bases, places like Vandegrift and Camp Carroll. They were part of the “McNamara Line” conceived to shut down enemy use of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. And according to Davis this simply wasn’t working. Marine battalions were being pulled back into defensive positions at the combat bases at night. This, he felt, was contrary to the way Marines think. Marines attack. They don’t hunker down. He saw combat being broken off when nightfall was eminent so that combat bases could be manned.

All that changed very quickly under Davis. The division would no longer be tied to defensive positions but, with helicopter support, would assume a highly mobile posture. Davis later stated,

“Forgetting about bases, going after the enemy in key areas-this punished the enemy most. … The way to get it done was to get out of these fixed positions and get mobility, to go and destroy the enemy on our terms, not sit there and absorb the shot and shell and frequent penetrations that he was able to mount.

… As soon as I heard that I was going, it led me to do something I had never done before or since, and that is to move in prepared in the first hours to completely turn the command upside down. They were committed by battalion in fixed positions in such a way that they had very little mobility. The relief of CGs took placed at 11:00. At 1:00 I assembled the staff and commanders. Before dark, battalion positions had become company positions. … Everyone else was expected to be in the field.”

So how did one of these high mobility missions play out? Armed with intelligence supplied by these recon patrols or through radio intercepts, the Marines advanced rapidly into the area of operations. Forward artillery positions, fire support bases, defended by a minimum of personnel would be established on key terrain features-hilltops. These bases were constructed about 8,000 meters apart, and provided ground troops with an umbrella of continuous artillery support. Ground units were inserted in the area and were able to move rapidly and largely on foot throughout the area to be searched-these were search and destroy missions!

Those serving in the 3d Marine Division found themselves confronting the enemy from the Laotian border to the coastal lowlands. There were no named battles, only named operations, endless patrols and missions which blended together. Those who fought, and bled and died did so in places largely forgotten by history, remembered only by those who served there, or by their families and loved ones.

The 4th Marines were responsible for patrolling the mountainous region north of Vandegrift Combat Base and south of the Demilitarized Zone. To the northwest of Vandegrift, 2 platoons of Company H, 2d Battalion, 4th Marines, along with elements of 3d Battalion, 12th Marines held Fire Support Base Neville, located atop Hill 1103. Ten kilometers east, additional elements of the 12th Marines, and a detachment from the 1st Searchlight Battery, held Fire Support Base Russell. Both bases had been carved out of the mountainous terrain in late 1968.

About the size of a football field, and bordered on one side by a steep cliff, Neville was described by Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Hopkins, as a “very rocky piece of ground often overwhelmed by low-lying clouds.” Said another Marine,

“I was shocked when I first saw it, a big, red, dirt splotch on the valley floor with bomb craters in every direction, all with water in them. The steel mat runaway was still in place and 6 aircraft parking revampments (sic). That was it, nothing else. As the chopper neared the base I looked out the starboard porthole and saw a little bald spot on a hill below. A thin trail wound up to it from the valley and wound away from it on the other side. I remember thinking how small it looked and it could only hold a squad or so on it … I was glad I wasn’t on that hill as we passed it. … Just then the chopper pitched to over to starboard and started corkscrewing down onto the hilltop.”

Although protected by concertina wire, listening posts, mines and sensors, Neville was regularly probed by NVA forces. Wrote one Marine in a letter home, “It’s getting weird around here. The gooks come up to our wire almost every night and then do nothing.”

Captain John E. Knight, Jr., commanding Hotel Company, described the early morning hours of 25 February 1969 as a typical night on FSB Neville. It was, he said,

“very foggy; it looked like something right out of a horror movie with fog drifting through the trees; visibility almost nil…The first indication we had that anything was out of the ordinary other than just normal movement was when a trip flare went off…”

Neville was under attack by some 200 sappers from the 246th NVA Regiment. According to Sergeant Terry Webber, “The earth trembled and the noise was deafening. I felt as if the world was ending that foggy night.” After infiltrating the concertina wire on the west side of the perimeter, the sappers crisscrossed that portion of the base occupied by 1st Platoon and Battery G’s #6 gun pit. Tossing satchel charges, they forced the defenders into bunkers, which they then destroyed.

Despite the destruction, the Marines began to rally. Sergeant Alfred P. LaPorte, Jr. commenced directing devastating counter-mortar fire and illumination on the assaulting force. As the Marines’ supply of mortar rounds became depleted, he fearlessly moved about the fire-swept terrain to ensure the rapid resupply of mortar ammunition. Awarded the Navy Cross for his actions, the citation reads,

“When an enemy round detonated in an 81-mm. mortar emplacement and ignited an uncontrollable fire, Sergeant LaPorte quickly directed the men of his mortar crew to evacuate the position and led them to a covered location, then returned and organized a firefighting crew to extinguish the blaze. Observing 2 wounded Marines lying in positions dangerously exposed to the North Vietnamese fire, he boldly maneuvered through the hazardous area and assisted his injured companions to a location of relative security.

As he reached the command post, an 81-mm. mortar round impacted in the vicinity. He unhesitatingly seized the extremely hot projectile and, despite severely burning his hands, threw it over an embankment, thereby preventing injury or destruction to nearby personnel and equipment. His heroic actions and calm presence of mind during a prolonged critical situation inspired all who observed him and saved the lives of numerous Marines.”

Said Gunnery Sergeant John E. Timmermeyer, in an interview done shortly after the attack,

“We beat these sappers, which are supposed to be the worst thing the North Vietnamese got…We beat these people not with air, not with arty, not with any supporting arms; we beat them and we beat them bad with weapons we had in our own company….M16s, M79s, or 60s or frags, everything we had in the rifle company….We didn’t have to have supporting arms. We did it without them.”

The command chronology submitted by 3d Battalion, 12th Marines clearly states, “Only through heroic efforts were the positions defended and the NVA finally repulsed.” In all, 14 Marines, and attached naval personnel were killed in action:

- HM2 Walter P. Seel, Moorestown, NJ

- Cpl Jeffrey M. Barron, La Puente, CA

- LCpl Thomas H. Mc Grath, Homewood, IL

- Cpl Gerald D. Zawadzki, Brooklyn, OH

- LCpl Steven V. Garcia, Phoenix, AZ

- HM3 John M. Sullivan, El Cajon, CA

- PFC Raymond L. Flint, Skaneateles, NY

- PFC Walter L. Lamarr, Sturtevant, WI

- PFC Samuel C. Macon, Delray Beach, FL

- PFC David A. Mallory, Huntsville, AL

- PFC Royce E. Roe, Pewaukee, WI

- PFC Carey W. Smith, Doraville, GA

- PFC Willie F. Smith, Houston, TX

- PFC Michael L. Zappia, Des Moines, IA

Ten kilometers to the east, Fire Support Base Russell also came under attack, obviously in an effort to destroy the guns located there. Once again, the attack began with a heavy mortar barrage, and supporting artillery fire from within the DMZ. Sappers from the 27th NVA Regiment quickly breached the northeast perimeter of the base. Said Captain Albert H. Hill, “In the first few minutes, the 81mm mortar section and the company CP, both located on the east and southeast side were decimated.”

In the initial moments of the attack, PFC William Castillo, worked feverishly to free Marines trapped inside bunkers. His Navy Cross citation states,

“Diving into his gun pit, he commenced single-handedly firing his mortar at the invaders, and although blown from his emplacement on two occasions by the concussion of hostile rounds impacting nearby, resolutely continued his efforts until relieved by some of the men he had freed. Observing a bunker that was struck by enemy fire and was ejecting thick clouds of smoke, he investigated the interior, and discovering five men blinded by smoke and in a state of shock, led them all to safety.

Maneuvering across the fire-swept terrain to the command post, he made repeated trips through the hazardous area to carry messages and directions from his commanding officer, then procured a machine gun and provided security for a landing zone until harassing hostile emplacements were destroyed. Steadfastly determined to be of assistance to his wounded comrades, he carried the casualties to waiting evacuation helicopters until he collapsed from exhaustion.”

Much of the fighting was hand-to hand. Another Marine, Gunnery Sergeant Pedro P. Balignasay was instrumental in minimizing the number of casualties, and in rallying the men on Fire Support Base Russell. According to his Silver Star citation,

“Sergeant Balignasay was momentarily stunned when thrown to the ground. Recovering quickly, he was immediately wounded by the detonation of a mortar round nearby. Ignoring his painful injuries, he raced through the fire-swept area to the point of heaviest contact and, organizing uninjured Marines, deployed them into effective fighting positions. Shouting words of encouragement to the men, he directed their effective suppressive fire against the advancing hostile soldiers and was instrumental in the Marines’ killing numerous enemy and successfully defending their position.

As he was moving across the hazardous terrain to ensure that all casualties were being treated, he was again seriously wounded, but resolutely assisted other injured men to covered places to await medical evacuation. After ensuring the security of the defensive perimeter and that all his comrades had received care, he then resolutely proceeded to the Command Post to relate the current situation before allowing himself to be medically evacuated.”

At daybreak, Marine air came on station. Only two officers and one staff non-commissioned officer remained. The Marines suffered 29 killed in action:

- LCpl Kenneth R. Gilliam, Lexington, KY

- LCpl Norman W. Kellum, Corpus Christi, TX

- LCpl Donald R. Lewis, Maysville, KY

- LCpl Larry W. Liss, Oroville, CA

- LCpl Gerald Przybylinski, Buchanan, MI

- LCpl Larry J. Sikorski, Fairmount, ND

- PFC Marion W. Lyons, Brentwood, AR

- PFC James D. Peschel, Boulder, CO

- PFC David L. Rutgers, Marshalltown, IA

- HM2 Kenneth Davis, Zanesville, OH

- 2ndLt William H. Hunt, Merritt Island, FL

- Cpl Tommy N. Miller, Bethalto, IL

- LCpl James D. Logan, Flint, MI

- LCpl Bruce A. Saunders, Roanoke, VA

- PFC Robert A. Coffey, Greensburg, KY

- PFC Michael L. Jenkins, Covington, VA

- PFC Randolph R. Ramsey, Williamsfield, OH

- PFC Allen M. Sharp, Covington, KY

- HN Donald K. Walsh, East Lyme, CT

- PFC Robert H. Brogan, Cincinnati, OH

- PFC Odell Dickens, Whitakers, NC

- PFC Douglas B. Forsberg, Minneapolis, MN

- PFC Juan Gaston, New York, NY

- PFC Robert A. McCarthy, Alden, NY

- PFC Norman R. Surprenant, Plainfield, CT

- PFC Robert H. Trail, Baltimore, MD

- PFC James E. Tucker, Miami, FL

- PFC George W. Weldy, Amarillo, TX

- Pvt Michael A. Harvey, Milwaukee, WI

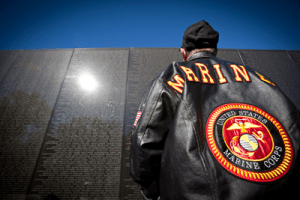

In a single night, 43 Marines died on those two remote fire bases south of the DMZ. Today, their names can be found on panel 31W of the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial. Their sacrifices have not be forgotten….A note left on the Virtual Wall, speaks eloquently of Hospital Corpsman Walter Seel:

“I first meet Phil (as he liked to be called) when I reported to Golf 3/12 3rd MARDIV in December of 1968. Being new, Phil took me under his wing and began to teach me the ropes of being a Corpsman in a combat zone. He was soft spoken and I never heard him raise his voice in anger to anyone. The Marines of Golf battery respected Phil and this made it easier to complete his job of being a Corpsman. The closeness between Phil and myself was like that of brothers, which in a way we were. Without Phil, I would have been lost.”

On 25 February 1969, Phil was killed on FSB Neville. He died doing his job as a Navy Corpsman. A piece of me died when I lost a great and gentle friend. As I am sure his family felt a deep sadness, I at the same time also felt this terrible sadness that has stayed with me since that day. Rest easy, Phil. You have completed everything you were assigned. Now you can take care of your Marines in heaven. Semper Fi.”

Another note was left on the Virtual Wall for PFC Robert McCarthy. Dated 28 May, 2006, it says, “REMEMBERED by his Mom.”

A friend once told me that as long as a Marine is remembered he is not dead. These 43 Marines, who gave their lives defending two fire support bases, hacked out of low jungle and mountainous terrain, are part of Marine Corps history. They will never be forgotten.

For more information: posts about Vietnam

- Least we forget: lessons for us from the Battle of Ia Drang, 26 November 2007

- How the Iraq and Vietnam wars are mirror images of each other, 7 February 2008

- Another note from our past, helping us see our future, 16 September 2009

- My movie recommendation for 2010: Vitual JFK (the book is also great), 7 January 2010

- Refighting the Last War: Afghanistan and the Vietnam Template, 27 March 2010

- Senator Jim Webb on the Vietnam Generation – Outstanding!, 25 July 2010

- Presidential decision-making about Vietnam and Afghanistan: “You have 3 choices, sir”, 5 October 2010

- History helps us learn from the past and overcome the ghosts of the Vietnam War, 3 March 2012

- Vietnam Has Left Town. Say Hello to our New Syndrome, 11 April 2012

.

.

My father served in the 3rd Marine Division in WWII from 1943 on. He then ended up in China for a few months before he came home. I still believe that it was the most signficant episode in his life, both for good and bad.. For him, there was never an issue about what the war was about and he never had much respect for those who managed to avoid combat.

Interesting, however, that with Vietnam he always advised young male relatives or friends to get a deferment. He always advised them not to go if they could manage it. He didn’t go into detail, nor did he ever make a political argument against the war. My take many years later – he died relatively young – was that he knew what war was, and made a decision that whatever the Vietman War was about, it wasn’t something that was worth a young man’s bearing that kind of burden for.

In any case, an argument can be made that America’s wars since WWII have been somewhat akin to the so called “cabinet wars” of the 18th C. European monarchies. As such, these wars are not only causing various harm to those who serve, but they cast a moral pale over the general population of those who don’t serve, but might have if things were different. Governments that conduct these kinds of wars give their populations no good choices.

Wikipedia entry for Cabinet Wars:

That’s a fascinating analogy! Two of the key differences are:

To push the analogy a bit, soldiers now still comport themselves and are inspired by the mentality of a “republican” levee en masse. Only to stop one day and discover that they’re being used by the government like they’re the soldiers of a cabinet war. Waking up from such a cognitive dissonance results in disorientation and anger. Hence the disquieting possibility of, as you say, a reckoning. Question: how would either of the major party candidates react if they were directly asked whether they are encouraging their own children to serve in the military? And would the political culture of our age regard such a question as being somehow inappropriate?

We must recognize two distinct classes of soldiers in America: the elite West-Point-educated officer corps, whose mommies & daddies know a congressman in order to sponsor them for an appointment (which is what you need to get into West Point), and the vast mass of impoverished poorly educated rural kids who join the army as the only escape from poverty.

Stats show that the best & brightest of the elite officer corps are leaving the army in record numbers. Source: “The Army’s Other Crisis: Why the best and brightest young officers are leaving,” Andrew Tilghman, 2007, The Washington Monthly. Meanwhile, recruitment is booming among the poverty-locked deep southern states of America: “In rural counties in Southern states, recruitment rates were more than 44% above the national average. In contrast, the rate of people joining the U.S. Army from Northeastern cities was nearly 40% below the national average.” Source: “Largest Share of Army Recruits Come from Rural/Exurban America” by Tim Murphy and Bill Bishop, 2 March 2009.

Thus, a backlash appears to have developed among the officer corps — but the poverty-stricken twenty-somethings in the deep south, who form the main pool from which the Pentagon draws its enlisted men, have increased their enlistment rates with the onset of our current recession. Moreover, as the recession worsens, those poverty-stricken southern-state boys are signing up in ever greater numbers.

The lawsuit filed in 2007 by veterans of the Iraq War alleging that the Pentagon deliberately withholds medical care and disability pay from injured vets does not appear to have affected recruitment rates. Meanwhile, stats show that only 23% of vets make use of the Army’s college bonuses. This is perhaps as we would expect, inasmuch as the people now volunteering for the U.S. army are so disproportionately poorly educated that few of them would qualify for college regardless of their financial ability to pay.

See a FM Reference Page for links to a wide range of articles about the Army’s ability to attract and retain good people.

Note that the recession and resulting high unemployment have eliminated the military’s difficulties attracting and retaining people. Now, as the reductions in force have begun, people who want to say are being kicked out.

I was at L.Z. Russell the night we were overrun, my memories of those who fought side by side with me will forever be part of my life. Reading the names of those k.I.A.s made me remember some of their faces and some of the things we had to do to survive the war.