Summary: Our reactions to films reveal much about us and our society. Why are there so many popular dark films based on our children’s comic? Why do critics object to films giving their characters horrific dilemmas? Here are my answers. Post your answers in the comments. Spoilers!

Boomers bummed by their failures

The Batman: The Dark Knight Returns shows a 50-year old Bruce Wayne again donning his cape, seeing that his decades of work has been in vain — with Gotham still a crime-ridden wasteland. The Dark Knight Trilogy

ends on an even darker note, with the Wayne fortune gone, Bruce fleeing to Europe, and his life’s work in vain.

The X-Men films end with the mutants almost exterminated both by internal conflict and human death squads — the evil mutants proven correct that humanity was their enemy. Cyclops was killed by the love of his life, Professor Xavier is a broken old man, Logan a limo driver, Xavier’s school closed and its children dead, and the dream of the X-Men program proven a folly.

In the second Avengers film, Age of Ultron, Tony Stark is a total fool, rolling out a superweapon containing alien components with minimal testing. No surprise, it almost destroys the world. Oddly, at the end of the film he is not in jail facing a trillion dollars in civil claims.

In Captain America: The Winter Soldier we learn that SHIELD and Nick Fury are evil — building flying death machines to control the world. Worse, Fury is incompetent, unaware that SHIELD has been infiltrated by HYRDRA.

The boomers love these films, perhaps because they mirror the failure of our generation. The Greatest Generation handed us strong cards. We squandered them, leaving the Millennials an America weaker in almost every way than the America we inherited. As children — so long ago — we read comic books overflowing with hope. Contemplating retirement and death we imbue the same characters with the pessimism born from our failures.

It’s not the best way to learn from a film.

Shown horrific choices, we use psychobabble to close our minds

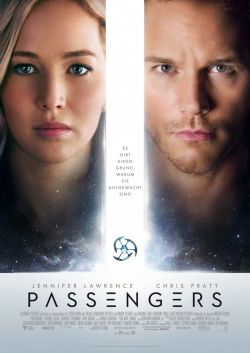

- Passengers (2016)

starring Jennifer Lawrence and Chris Pratt.

- Beauty and the Beast (2017) staring Emma Watson and Dan Stevens.

Fiction allows us to imagine ourselves confronted with situations that test our values. One of the most famous is “The Cold Equations” by Tom Godwin (1954; see Wikipedia) — about a spaceship pilot facing one of the harshest decisions imaginable. Two recent films explore similar situations.

In Passengers a man awakens prematurely from suspended animation during a centuries-long trip, with no way to re-enter. What would you do when facing a lifetime alone? Would you awaken someone to keep you company, however morally wrong?

For the woman awakened, how might she regard this man who loved her? He woke her unjustly, but holding a lifelong grudge against him would not help either of them. They were a world of two, alone in space. Critics hated it, chanting “Stockholm Syndrome, Stockholm Syndrome”. As if this psychobabble would help either of these people in this terrible situation.

Disney radically changed the original “Beauty and the Beast” story by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve (1740, see Wikipedia). Two changes dial up the tension. In the Disney versions, Beauty was held against her will. In the original the Beast says “If she comes at all, she must come willingly. On no other condition will I have her.”

Second, Disney has the rose act as a timer. When the last pedal falls, the Beast will remain a beast for the rest of his life (it is even worse in the 2017 film: the servants will die, becoming objects).

Desperate as the clock runs out, the Beast kidnaps Beauty. He knows it is wrong, but has no better options. What would you do? He wins his gamble when Beauty sees through his animal exterior to the prince within. They fall in love. Is there any other possible happy ending? Showing the empathy expected of leftist ideologues, the critics condemn the Beast and chant “Stockholm Syndrome, Stockholm Syndrome” about Beauty. It is an impermissible outcome for people to see. Both life and film must be ideological correct (our critics love their version of socialist realism).

We can learn about ourselves from these stories, but only if we imagine ourselves in the shoes of the protagonists — and honestly ask how we would react. We learn nothing by judging the characters in films excerpt the cheap thrill of self-righteousness.

For More Information

If you prefer a nice romantic comedy, without the deep questions, here’s an interesting trailer: “The Silence of the Lambs as a Romantic Comedy“.

If you liked this post, like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter. See all film reviews, and especially these…

- Recommendation: nine of the best American romantic films.

- Why have our movies become so dark, showing a government so evil?

- Review of Dr. Strange: a good film misunderstood by the critics.

- How does The Hunger Games compare to other classic stories of children fighting children?

- “Mockingjay” shows us a path to reform for America. A great movie, but bad advice.

- James Bowman reviews Disney’s “Frozen”, & its frozen ideology.

- The Great Wall is a fun film showing us a great Chinese-American future.

Trailer for passengers

In general, I feel that your comments are spot-on but I would like to address the Dark Knight trilogy in particular because I believe it is different from the rest of the movies.

The trilogy begins with “Batman Begins” which is a crowd-pleasing story that contains all of the sins you have detailed.

The story takes a dramatic turn in the “Dark Knight,” ending with Batman creating a lie about how good a person Harvey Dent was and using that to try to impose his own version of Utopia on Gotham without the consent of the people. You mentioned the “Cold Equations” (which gave me nightmares for a week after I read it), the Joker is the ultimate version of the “Kobiashi Maru” (Star Trek’s no-win situation) and Batman, because of his personal demons, doesn’t do very well (in fact, about the only person who handles the challenges presented by the Joker reasonably well is a hardened convict). Ignoring the ridiculously over the top plot details (which is, admittedly, very hard), the Joker comes very close to breaking Batman completely, using his own weaknesses against him.

By creating the legend of a selfless Harvey Dent, Batman became a bit of a super-villain, imposing his own needs and desires on the city with the feeble excuse of trying to make it a better place, at least in his mind. The Joker would have used the same arguments if asked. Batman should have told the truth about Harvey Dent and asked people to feel compassion for the man but he is too much of a loner and too distrustful of other people’s maturity. About the only thing that Batman gets right in this movie is that the people should NOT put their faith in superheros and retires.

I have real problems understanding why this movie was so popular and agree with you about the Baby Boomer generation’s response to the movie.

The redeeming feature of the trilogy is the last movie. Again, you have to ignore the ridiculously over the top scenes and plot details to get to the core meaning of the movie. The lie that Batman created at the end of the “Dark Knight” has been used to pass a series of draconian laws that have temporarily cleaned up the city but lies always unravel and cause more problems in the end. The tables are turned and the convicts, many of them suffering from severe mental health issues, are in charge of the city (don’t pay too much attention to the details, they are too stupid). Batman comes out of retirement after 8 years and, without proper preparations or training, is defeated and imprisoned. As in the “Dark Knight,” common people are tested by the criminals and mostly found wanting and die.

The key difference between this and other superhero movies is that because Batman isn’t around, Gotham’s citizens have to start thinking and acting to take back control of their destinies. Bruce Wayne, stripped of every remnant of Batman’s aura of invincibility and finally confronting his own demons and past mistakes, needs to decided whether to live and on what terms. I personally have gone down that road more than once, (not near as far as Batman, thankfully) and the amount of willpower and thought it takes to recognize your own mistakes, to grow and heal, and to find a way past your mistakes to redeem yourself with your fellow humans is what makes somebody a true hero.

When he finally escapes, Batman doesn’t seek to destroy the bad guys for the city, he just seeks to remove the one way the bad guys have of controlling the people of the city (which Bruce Wayne unintentionally created). It is up to the citizens to control their own destiny. For example, Jim Gordon and a team of police officers take control of the bomb before it can go off. Batman confronts the BBG (big bad guys) to distract them from the bomb, makes some mistakes, and loses to Bane again. The only reason he survives is that Catwoman has also grown as a person and seeks to help him instead of saving herself.

The obligatory “saving the day” scene at the end of the movie is only tolerable for two reasons:

a) It totally destroys any chance that Gotham’s citizens will ever look to Batman to save them again

b) It gives Bruce Wayne a way out of the trap he created for himself when he created the Batman

I was unhappy with the citizens of Gotham choosing to rebuild the law enforcement part of their social image around Batman, it felt like they were replacing the impossibly pure memory of Harvey Dent (which was a lie) with Batman but at least it was their own choice and was closer to the truth.

You write that “the Wayne fortune gone, Bruce fleeing to Europe, and his life’s work in vain.” All of your statements are true but:

1. Bruce Wayne didn’t use his fortune very well and he gave the remnants to somebody who suffered a great deal because of his mistakes. It is possible (even likely) that Alfred will use the money better than Bruce did

2. By the end of the last movie, Bruce needed to start over and hiding in Europe and earning money using his own skills rather than inherited money was a good way to go. As the movie showed, he did okay for himself. I wouldn’t be surprised if he teamed up with Selena Kyle to become jewel thieves.

3. As you constantly (and correctly) point out, the weakness of superhero films is that they encourage people to be passive and wait for somebody to save them. Bruce’s life’s work was in vain from the moment he put on the mask. It just took 3 movies for him to realize it and fix the problem

Look at the comments that the composer Hans Zimmer made comparing the Dark Knight movies and “Batman vs. Superman”:

“For me, the Christian Bale character was always completely unresolved. It was always about that moment at the beginning of the first movie, where he sees his parents getting killed. It was basically arrested development. The Ben character is more middle-aged; he seems to be grumpy as hell, but I didn’t feel the pain that I felt in Christian’s performance. And it was that pain that made me interested.”

That pain was what made the “Dark Knight” Batman and moving beyond that pain required Bruce Wayne to step beyond Batman.

Pluto,

Thank you for your thoughtful comments, going far deeper than the simple point made in this post.

Myths are white boards on which we tell our own stories. I saw the Batman saga as that of a society (Gotham) broken beyond its ability to regenerate. Bruce Wayne saw that the standard good citizen — leaders and philanthropist — model used by his father would not suffice. Becoming Batman was intended to push back the forces of chaos to buy time for Gotham to heal, after which he could retire.

The Dark Knight saga re-invented that to show Batman as a failure. The Dark Knight films expanded that into complete failure, leaving behind nothing. No heir to the Wayne line, no fotune, no mansion, Wayne Enterprize bankrupt. Total failure.

In that respect it is exactly like the X-men film saga. A story for Boomers about Boomers.

Hi Pluto,

Wow! Nice analysis. Thank you, Fabius, for letting this epic stand, as I know there is generally a limit on posting lengths.

Bill

I guess I don’t see it that way. You’ve got two tired franchises, where the ‘goodies’ get to win every time, and only the people in the red vests get permadeath. So producers, writers, directors think we need a good dose of the nasty, something that moves things into a space where there’s no possibility of a good outcome. Apparently.

But if there’s one thing a couple of decades reading comics taught me, there’s no such thing as an unhappy ending. Yes, you may *think* Cyclops is dead, but all they need to do is remove the garlic from his mouth and the stake from his chest and he’ll rise again.

Eventually I got sick of it and stopped reading comics. All those issues that promised real drama, but delivered the equivalent of Dallas pretending that an entire season was a dream.

Franchises looking for a dramatic conclusion, painfully reluctant to let go and move on to something new when its clear that the story may be moving, but is already long dead and just looking for brains. In comics so the movies. A pause, a re-invention story, and another series or two awaits.

Last X-Men comic I read was something written by Joss Whedon that left Kitty Pryde de-materialised in a missile speeding out of the solar system. The one thing I can bet you is that it’s NOT the last we’ll see of her. She’ll have been rescued by Galactus, or Silver Surfer or the Kree or those aliens professor X was always hanging out with. Or something. And round we go again. It’s not just cowards that die a thousand deaths, heroes do too, as long as the money keeps coming in.

Gotta feel sorry for Cyclops, being killed by the girlfriend. Twice. I can only hope the guy receives counselling when he gets back. :-)

Steve,

“But if there’s one thing a couple of decades reading comics taught me”

While interesting, that’s not relevant to this post — which explicitly discussed the films, not the comic books. I started with the graphic novel The Dark Knight because that initiated the new era. The films are a mass social phenomena (seen by 50 – 100 million people), and so tell us much about our society.

The comics are a literary niche (individual series read by a few thousand or tens of thousands of people), smaller than TV fan fiction. That is, the “shipper” websites for individual TV shows have larger audiences than most comic book series. Their cultural significance is nil.

Hi FM and all,

I generally concede the argument, but I put Frank Miller’s work out of the cinematic mix — it spoke to me differently reading it back in the day. Perhaps I need to read it again. If FM (Frank Miller — Fabius Maximus — have you ever seen the two in the same place? Hmm…), changed the ending, then this won’t stand. However, as I recall, it’s actually Fabius Maximumish in its way.

Spoilers spoiler spoilers the summary of Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller et el.

It’s the standard Batman backstory, and as you say, Gotham is still a hellhole despite years of vigilantism and Commissioner Gordon’s best efforts. Bruce cracks, and puts the mask and cape back on, and makes matters worse as he reinvigorates the Joker. We see in Wayne’s first encounter with the Mutant Leader, he is no longer capable of simply overwhelming his opponents or his demons. And, as if for the first time, he learns something about the nature of reality. It’s really not all about him and his need for revenge and black or white justice.

The next step (and if I don’t get this right, my memories are almost as old as the 30th anniversary would indicate as possible) in the story of bringing Robin on board. Robin is a girl from a broken home with no prospects, and while she knows she can’t go it alone, she figures she has to, and helps save Batman from the Mutant Leader. Robin 2.0 becomes a partner and student rather than the expendable tool that was Robin 1.0.

As the story continues, Batman becomes more contemplative, more expansive, more inclusive (Gordon, Green Arrow, Mutant cast-offs, etc., ) and realizes that he can set himself and his friend Clark Kent Superman free by beating him in combat at the expense of his life. Classic savior trope. He’s still a control freak and perfectionist, and refuses to allow death to mean that he dies, and is upset that Clark found out his game. Such a great couple of panels at the funeral. He’s not the angry vigilante of his youth, but a founding father of a movement to lead a community to a better place.

How many stories are told these days where old men aren’t allowed to just check out, but need to man up and help lead the next generations into a better tomorrow?

These comics (if you can call them that) resurrected the whole Batman franchise in its many forms. But none of them ever got what made this series so great: Bruce Wayne was a different, better man at the end; Batman didn’t just eliminate a symptom, he provided a cure (Superman, Green Arrow, Robin, Mutants, Gordon, etc.), and provided hope that free people could unite to make the world a better, or at least, livable, place. Batman can’t do it for “them”, only they can do it for them.

Alan Moore’s Watchmen is literature. Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns is religion.

Read them *both* in print. They should teach them in school.

Regards,

Bill

FM was very kind to my review of the Dark Knight movie trilogy. My point was that the last movie in particular showed the weakness of the “wait for the superhero to save the day” theme that runs through all such efforts and that superheros and supervillains impose their will on reality more for internal reasons than for the benefit of the common people.

FM made a far better and bigger point by showing me that although the general themes of the Dark Knight were true, why should society as a whole embrace failure in its myth-space? The major themes in a society’s myth-space tend to become reality over the next 30 years. The original Star Trek series is a classic example of this. Dreaming of failure and admiring dreams of failure eventually brings about failure in reality.

I find myself agreeing with FM that the cause of this problem is the Boomers sense of failure and futility. America today is generally a much better place physically than it was 40 years ago (cleaner air and more equal enforcement of justice are just a couple of examples) but socially it is somewhat worse primarily due to automation, demographic changes, and the income inequality successes of the 0.01 percent. The Boomers felt like the chosen ones and didn’t work hard to make their bigger dreams come true. Now they are sliding into retirement feeling dissatisfied and like they didn’t accomplish much, which is generally true.

Although I am a boomer by birth, I have always felt a loathing for boomers in general and have many more friends in the Millennial generation (most of them don’t like the title and feel that it is being forced on them by the Boomers, which is generally true). They know that they are, by and large, in a worse spot than their boomer parents were at the same age but they are more realistic in their plans and know that they will have to work hard to achieve them.

I am writing as a woman commenting on the last two: the new Beauty and the Beast and Passengers. I don’t understand what you are thinking. Certainly the Beauty and the Beast version in which Beauty is held against her will is about Stockholm Syndrome. It reminds me of Patty Hearst and the SLA. It is not a consensual relationship if one are being held against one’s will. I think the issue is that these stories should not be presented as romantic love stories.

Perpetuao of carthage,

“It is not a consensual relationship if one are being held against one’s will.”

I think everybody is clear about that. The question is to what degree to which that stripe the woman of all agency — so that her decisions one released from captivity are considered invalid — like those of a minor or someone not mentally competent. There is a long history of declaring women to have no agency on quite trivial grounds. The reaction to these films is just another example of that.

“I think the issue is that these stories should not be presented as romantic love stories.”

That is legitimate question. But it is not the issue raised in this post — which is about the dilemma faced by the Beast and his servants in B&B and the awakened passenger in Passengers. Your comment demonstrates my point: people look at the ideology of the story and ignore the primary question raised by these stories: what would you do in that situation? I’d like to hear your answer.