Summary: One function the FM website performs for readers is assembling data into pictures that show how our world works. Today we look at three factors of American households: income, spending, and debt — and how they relate to one another. It’s not a pretty picture, but one we can change if we work together.

.

One powerful measure of America’s recovery from the crash is real disposable personal income (aka after-tax income). Let’s look at it in pure form, after adjusting for population growth and inflation: Real Disposable Income per capita. It has risen a pitiful 0.7% per year over the five years from the start of the recession. Slow movement in the right direction.

.

But that’s an aggregate number, and such numbers hide as much as they reveal. How has this tiny income gain been shared? Have all classes gained income? Note inflation (CPI) was 1.5% in 2010, so gains less than that are negative in real terms.

.

.

Let’s take a longer perspective on income distribution. Anyone paying attention knows that the 1% have gained massive economic and political strength, starting with the Reagan Revolution — continuing year after year since then. It’s paid off big for them, as shown in this graph (it shows growth in real after-tax income).

.

How has the top 1% done so well? By grabbing a larger share of the national income from the bottom 80%.

.

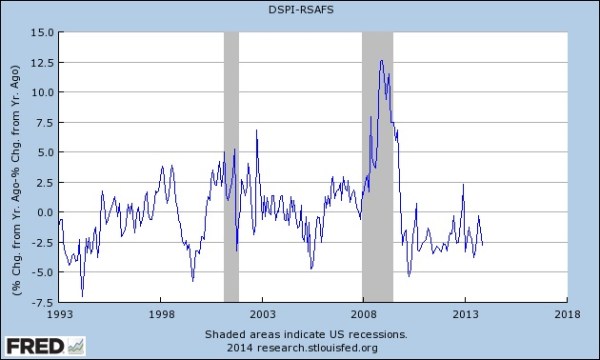

How has the middle class coped? By increasing spending faster than their income. The following graph looks at percent change YoY in Disposable Personal Income minus Retail Sales (including food services). Income and spending grew roughly together in 1994 – 2007. Spending crashed faster than income in 2008. Since then spending has increased faster than income. When the going gets tough, Americans borrow.

.

For more about this see Rising consumer debt driving the recovery: boon or bane?, 10 November 2013.

This strikes me as quite mad (but then so many aspects of US public policy look mad). But it works well for the 1%. Borrowing to maintain our lifestyle keeps the people quiet and the factories running. Our debts make us work hard.

How will it end? With a bang or whimper? Boom or bust? We get to write the ending to this story.

For More Information

(a) Authoritative reports:

- Census data on household income by quintile: see table H1 and H2.

- Graph of that data: change in real household income by quintile by year

- Trends in the Distribution of Household Income Between 1979 and 2007, CBO, October 2011

- “A Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality“, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 5 December 2013

- National Report Card on Income Inequality, The Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality, January 214

- Distribution of Household Income and Federal Taxes: 2010, CBO, December 2013

- The most current data: “Household Income Trends: November 2013“, Sentier Research, December 2013

(b) Other posts looking at the economy today:

- A look at the state of the US economy. Join me in confusion!, 13 July 2013

- Let’s reflect on the course of the course of the US economy. Not a pretty picture., 8 September 2013

- Do you look at our economy and see a world of wonders? If not, look here for a clearer picture…, 21 September 2013

- The great monetary experiment enters a new phase, with America as the stakes, 27 October 2013

- The key to understanding the future of QE3, and the future of our economy, 12 November 2013

- Larry Summers gives us the bad news. Worse, the only solution is more of the same., 20 November 2013

- The astonishing news about the December jobs report: it shows continued slow growth, 13 January 2014

(c) Other posts about US debt

- A certain casualty of the recession: the US Government’s solvency, 25 November 2008

- America is rich and powerful because we can borrow. Will this debt build a stronger America?, 5 June 2012

- America’s strength is an illusion created by foolish borrowing, 10 October 2012

- Rising consumer debt driving the recovery: boon or bane?, 10 November 2013

.

.

Real household incomes are declining for a majority of Americans, while real final sales to domestic purchasers have just recovered to pre-crisis levels.

The conclusion I draw is that most Americans are experiencing a depression, while the elites blithely increase their spending. N.B. “Final sales” does not include capital goods, intermediate goods, etc., so I am presuming it includes Consumption + Government, and we know G employment has declined under O.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/MEHOINUSA672N

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/A713RX1Q020SBEA

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/USGOVT

cheers,

benign

Benign,

You cannot accurately make that statement on the basis of the data you show. Which is why I warned in this post about the misuse of aggregate data.

That the median drops does not mean that it drops for *most* Americans. Disaggregated data — more granular — is needed to show that. Such as that in the reports I cite, which look at income quintiles.

Also, the BEA’s personal income data is insufficiently accurate for this kind of analysis. Which is why experts rely on the far more accurate IRS data, unfortunately available only after a lag. The reports cited here use 2010 data (and earlier).

Benign,

Here is an article explaining why the change in median income does not mean that the income of most Americans has declined.

Here is the actual census data on household incomes by quintile by year — see tables H1 and H2. Household income of all quintiles up since 2002; of top 4 quintiles up since 2007.

Here is a graph showing the Census data.

Larry Summers has an article that does a detailed breakdown on the inflation-adjusted cost of goods and services. Summers shows that while trivial items like TVs and iPhones have gotten much cheaper after inflation since 1984, the necessities like food, housing, medical care and college tuition have grown exponentially more expensive in real terms.

Here’s a summary, but the entire 2013 Martin Feldstein Lecture is worth reading.

Thomas,

I am a fan of Summers (too smart to a Fed Chairman, apparently). But this analysis is untypically shallow.

There is a large body of work about the dichotomy between goods/services that are declining in price …

(A). tradable (can be done more cheaply in emerging nations),

(B). subject to automation (now manufacturing, but increasingly affecting other fields), and

(C). high component of labor can be done by low-skill immigrants.

and goods/services that whose prices are stable or rising — due to some combination of characteristics (most often regulatory barriers and a high level of labor) and winner-take all competition (e.g., top authors, stars, CEO’s, etc).

The effects of this are very complex. Beneficial to those whose income is not affected (e.g., doctors), upper middle class (get to have servants again). Detrimental to those whose wages are decreased — or whose jobs are destroyed.

Another good source on this topic, although the researchers obscure the data a bit, is the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances. I have copies of the 1998 through 2010 reports and laying out the reports beside each other paints an interesting picture with far too few data points to be used as a primary data source.

The numbers for income agree with FM’s numbers but he numbers for net worth are considerably more interesting in my opinion.

They show that the net worth of the lower part of the middle class peaked in the 2001 survey and have been declining since. The middle middle class peaked in 2007 and took a 25% hit by 2010. The upper middle class also peaked in 2007 but crashed 37% by 2010.

Before 2008 the middle class had been elongating as the lower middle class slowly sank while the upper middle class made considerable gains. In hindsight, this was probably mostly due to the housing bubble. By 2010 the middle class had roughly the same shape it had in 1998 but all three groups had a markedly lower net worth.

I am eagerly awaiting the 2013 survey results but they aren’t due out until about a year from now.

Net worth numbers for the bottom 80% of the population mean very little because essentially all of the net worth of people who aren’t millionaires boils down to the value of their house, and that plummeted after the 2009 subprime financial meltdown. But the economic reality remains that the so-called “net worth” signified by the alleged value of your house means nothing in real terms. You can’t tap that alleged “net worth” because you still need some place to live. And in today’s market, most people probably couldn’t sell their homes even if their mortgages aren’t underwater, because the loan requirements banks have placed upon home buyers are now so strict.

Meanwhile, I think Summers’ point valid, and here’s more evidence: “More Losers Than Winners in America’s New Economic Geography,” 3 January 2013, The Atlantic magazine.

Pluto,

I agree that it’s important to look at concentrating wealth in addition to income. In many ways wealth is more important than income, and this will become increasingly so as the 3rd industrial revolution advances (as it increases returns to capital while probably putting people out of work).

Unfortunately data on wealth is of far lower quality, as we have no equivalent to the IRS legally forcing people to disclose accurate numbers. There is some good work in this field, such as “The Asset Price Meltdown and the Wealth of the Middle Class“, National Bureau of Economic Research Digest, April 2013 — Summary:

Fab –

You refer me to an article that says the decline in real median household income is not really important because it is caused by a decline in the employment to population ratio. WTF?

You refer me to charts that are not inflation adjusted showing increasing nominal household income to refute my (true) assertion that real median household incomes are falling. WTF? If you looked at Short’s inflation adjusted disaggregated charts they support my point entirely.

And on Larry Summers–he is in the same category in my mind as Bob Rubin and Eugene Fama–rigid ideologues willing to say anything to justify “free markets” (because “they are efficient”). This gambit gave us unregulated derivatives and the financial crisis. These guys are Wall Street whores.

The rich world is suffering a bout of hard heartedness that manifests in those with power and status expropriating more and more for themselves and their children, and marginalizing and in some cases literally killing the lower classes (many say this is one of the hidden objectives of Obamacare). We have glorified greed, we worship money. Democracy is dead; the public is in an electoral strait jacket–on this we agree. The elites get their way, the rest be damned.

Always a pleasure to disagree with another grumpy old man!

cheers,

b9

Benign,

(1) “You refer me to an article that says the decline in real median household income is not really important because it is caused by a decline in the employment to population ratio. WTF?”

The article explained how median income can change while wages rise, as people lose jobs and drop to the bottom quintile. As I said, compositional changes can pull the median down while the income of the average person remains the same or rises.

(2) “You refer me to charts that are not inflation adjusted showing increasing nominal household income to refute my (true) assertion that real median household incomes are falling.”

The changes are quite large, esp given the low inflation during the past decade – and more so since 2007.

(3) “If you looked at Short’s inflation adjusted disaggregated charts they support my point entirely.”

Take a ruler to it. None of those lines show declines.

(4) “And on Larry Summers”

He is a loyal servant of our plutocrats. That’s how one rises in core economics field (e.g., Wall Street, Treasury, Fed, etc). Much as one rises in the geopolitical field by serving DoD and the defense vendors.

Correction:

“None of those lines show declines.”

Outside of the recessionary period.

L. Randall Wray touched on spending here:

“The productive sphere is made more stable by the spending habits of workers. Workers must spend most of their income to acquire the necessities of life—through the purchase, primarily, of producibles. Advertising and the propensities of conspicuous consumption and pecuniary emulation help to ensure that even if wages are in excess of the income required to satisfy biological necessities, workers still spend most wages on producibles. It is this consumption behavior of workers that “grounds” capitalist economies by imparting stability to the production of consumer goods…”

Spending on producibles is a deep part of our culture. We inculcate ourselves through advertising and facile innovations, shoving down society’s throat the need to have the newest thing regardless of income. No worries with cheap credit, right? The point here is that we can’t expect our society to change its culture just because one element has changed (income) when another arises to take its place (cheap credit). Short term the effect is minimal. It’s in the long term where credit eats the debtor. But, all this allows society to continue on its path towards…?

Wray also addresses the fact that our spending habits ‘impart stability’ in our system. Demand is already too low, but if people stopped borrowing, then production could/would crumble. In other words, Americans must borrow to prop up the system that is only destroying them.

Lastly, the fact that Americans have to borrow to keep up the normal rates of spending is highly indicative of an actual, not nominal, decrease in income. This goes back 3+ decades, not just since the great recession.

Jayray,

There are two schools of economics. There is the quantitative form, where economists marshall data and use statistical analysis. Then there is the philosophical school, where people confidently make statements without hard evidence.

(1) Wray nicely states a widely held opinion. It is usually stated as fact, without evidence. Yet it seems unlikely to me.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs suggests that people naturally have needs above those of sustenance, needs existing without advertising. History provides ample evidence of this. Most societies across time, around the world, have a class of people enjoying ample surplus income. How many of them use their excess incomes mostly for good works, while leading lives of contemplation rather than consumption?

In fact aristocracies (using the term broadly) usually engage in forms of conspicuous consumption. Without advertising.

(2) “Lastly, the fact that Americans have to borrow to keep up the normal rates of spending is highly indicative of an actual, not nominal, decrease in income”

I believe you will need actual evidence for that. Specifically that over the past “3+ decades” large numbers of people accumulated debt while having a constant level of spending. Most indicators show that people used debt to increase their spending. Look at the number of households with more and larger cars, more kinds of goods, children going to college, and larger homes.

With FM’s grossly inadequate response to Larry Summers’ article and to the marshaling of considerable charts and stats, we see a perfect example of modern America’s defective OODA loop.

FM can see the charts but he chooses to pay no attention to them. FM can read the economic stats but he prefers to come up with increasingly ingenious and far-fetched explanations for why they don’t matter. This is the same mindset Americans exhibited when bogged down in Vietnam, or when faced with a persistent epidemic of off-the-charts gun violence, or when trying to grapple with America’s collapsing fee-for-service private-for-profit medical-industrial system.

The OODA loops is broken. Unable to orient himself, the hapless Americano resorts to ever more absurd rationalizations: “We have to fight them over there so we don’t have to fight them over here!” “Guns don’t kill people, people kill people!” “Nationalized single-payer health care is socialized medicine and the first step on the road to serfdom!”

FM’s rosy take on the current state of the U.S. economy contrasts markedly with worries by smart knowledgeable people like Larry Summers that the current ongoing recession may represent “the new normal” for the U.S. economy — Summers calls it “secular stagnation,” Krugman calls it “a permanent slump,” but whatever it is, if it continues, it spells the end of the American middle class. And without a middle class, you can’t do democracy. Instead, you get Mexico, a country that holds elections but is in reality owned and controlled by the 35 most wealthy families.

And what is FM’s response to these statistics and charts?

“Prosperity is just around the corner!”

Herbert Hoover tried that one. If memory serves, it didn’t end well.